1967 and After

|

| Coach Fran Koenig talks to her basketball team, 1970s |

Women's intercollegiate sports slowly became a regular part of the athletics program at CMU in the years after WWII. 1967 could be considered a landmark year, when the Central entered its first organized league for intercollegiate women's basketball. The team played only four games in its opening season.

Within a decade, CMU women's athletics had grown to include swimming and diving, basketball, volleyball, and gymnastics. The basketball season in 1976 included more than 20 games as well as post-season play. Central's women's teams competed in the Midwest Association of Intercollegiate Athletics for Women (the MAIAW). At this time, women's sports weren't governed by the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA); it wasn't until 1981 and 1982 that the NCAA took on women's sports.

The late '60s and early '70s also saw the hiring of two legendary coaches: Fran Koenig and Marcy Weston, both of whom were instrumental in supporting women's sports at CMU and nationally. CMU hired Fran Koenig, a women's basketball coach and physical education professor, in 1969. Three years later in 1972, Marcy Weston joined the athletics staff as a field hockey coach. Her role expanded to head volleyball and basketball coach within only a few years, a testament to her skill and passion for coaching. Koenig transitioned into athletics administrations by 1975. Both women served in crucial roles in women's athletics on the precipice of the passage of Title IX, helping to usher in a new age of women's sports.

In 1972, early in the tenures of Koenig and Weston, Title IX of the Federal Civil Rights Act was enacted. It prohibited sex-based discrimination in educational institutions that received money from the federal government; although it explicitly mentioned education, interpretations of this act encompassed the totality of the educational experience, including extracurricular activities such as athletics. Many would argue that the progress seen in women's sports in the past fifty years has stemmed directly from Title IX. It could also be argued that women across the country, such as the leaders at CMU, were the key fighters for progress, with Title IX serving to support them in their efforts.

|

| High jump at a CMU track meet, 2001 |

Title IX's passage in 1972 did not usher in overnight change. During their time, Koenig, Weston, their fellow coaches and administrators, and countless athletes fought to even out the playing field incrementally, not transform the entire landscape instantly. Their initial requests were small steps in the big journey toward equality:

- Hotel room accommodations for away games. When Weston started coaching volleyball, she asked players who were from the geographic area of the opponent’s team if the players could bring sleeping bags and stay at those players’ houses. Where a premier men's team might place 2-3 players to a hotel room on road trips, the women’s teams offered to sleep 4-5 women to a hotel room.

- Chartered travel to and from away games. Even as the twentieth century was coming to an end, rather than taking a bus with a dedicated driver, coaches and trainers of women's teams often got behind the wheels of vans to drive their teams to competitions. After driving six-to-eight hours to an away game in Ohio or Illinois, the coaches and trainers would then have to gear up to coach. And after the game, the coaching staff drove the team back to Mount Pleasant, which might be an uncomfortable ride after a disappointing loss. By the 2010s, when Sue Guevara was head coach of the Women's Basketball program, she pushed for charter flights for the long trips during the middle of the week, just like the men's team received, to make sure her student-athletes had the same opportunities to get back to CMU and be ready for class the next day.

- CMU-purchased meals for the women athletes. Men's programs had access to university-sponsored meals for their athletes, while women were relegated to providing their own meals. The demand for equality in nutrition wasn't about receiving the same exact amount of food or the same dollar value of food—nobody would argue that the women's soccer team needed as much food as the football team—but about having the same opportunity to offer the team one or two meals per day, just like the men's teams.

- Access to equal facilities and equipment. Women’s volleyball played in Finch Fieldhouse for seven years after Rose Arena was open. Even after volleyball moved to Rose Arena, the team used outdated equipment that most other Division I schools had phased out years prior.

A year after the enactment of Title IX, the Rose/Ryan Center opened, named in part after Grace Ryan, a long-time and well-respected CMU women's physical education professor. A precursor to the McGuirk Arena and Kulhavi Student Events Center, the Rose/Ryan Center hosted both men's and women's basketball home games. However, women's volleyball continued to play in Finch Fieldhouse until at least 1979, and women's field hockey didn't move from the Alumni Field to a facility near the stadium and arena until 1976. Women athletes and coaches for these organizations had to push to be hosted in the same or similar facilities as men.

|

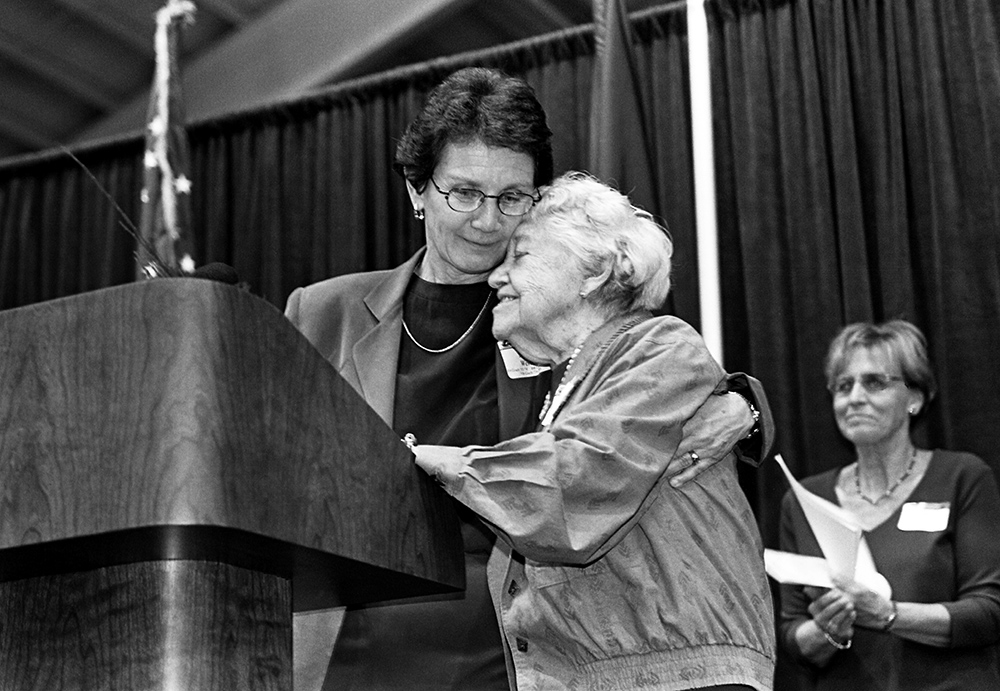

| Varsity letter ceremony, 2000 |

With advocacy and persistence, disparities between men and women have slowly been reduced. A major symbol of athletics success at a university is earning a varsity letter. Prior to 1985, women at Central couldn't receive their varsity letters, a tradition men had taken part in for decades. In 1985, the tradition was expanded to include women. But that still left out generations of previous athletes.

In 2000, Fran Koenig, Marcy Weston, and others arranged for all pre-1985 women's athletes to finally receive their varsity letters. In the end, 235-250 women earned their belated varsity letters at the October 13th event. Fran Koenig, a mentor of many of the honorees, passed away the day before, making for a very moving and emotional event. Marcy Weston remarked, at the time, “It was an electrifying evening. It was probably the most heartwarming, memorable event I've been to." She added, “The aura and energy in the room. I don’t know if I’ve ever experienced anything like that in my 28 years at CMU.”

Just a few years before CMU began awarding varsity letters to women, Central's female athletes made the move to compete under the umbrella of the National Collegiate Athletic Association, which had been considered the powerhouse of men's college sports for decades. Before 1982, Central's women's teams competed in leagues separate from the NCAA. Continue reading to discover how CMU's athletics leaders helped CMU women's athletics move into the NCAA.