Combatting Sexual Violence

When Central Michigan University opened the doors to the first residence hall, Ronan Hall, it was separated by gender, like many aspects of college life at the time. In 1924, only women could live on campus at CMU, and it wouldn't be until 1939 that men joined them (and not until 1971 that co-ed living was permitted). Although only a small aspect of the history of CMU, Ronan Hall represents a time before college campuses seriously challenged the ways they engaged with gender—nearly half a century before the passage of Title IX, 61 years before CMU women received Varsity Letters, and 87 years before the nation began to consider sexual assault and harassment to be an issue of gender equity. Today, Title IX not only covers women's education and participation in extra-curricular activities, but also equal access to safe campuses and justice in the face of sexual assault and harassment.

|

| Let's End Campus Sexual Assault Meeting, CMU, 2016 |

Sexual violence as a component of Title IX did not take national spotlight until the 21st century, but the first attempt to use Title IX to combat sexual harassment came only five years after the legislation's passage. A female law student named Catharine MacKinnon helped a group of students sue Yale in 1980, arguing that protections against sex-based discrimination should go beyond admissions and athletics, and encompass sexual assault and harassment as forms of sex-based discrimination in themselves.

MacKinnon and the students lost the lawsuit on a technicality. However, the court agreed with their line of thinking: sexual violence of any form at a college or university should be considered a Title IX violation.

The lawsuit preceded some of the first research on the prevalence of sexual violence on college campuses. In 1987, the National Center for the Prevention and Control of Rape found that over 1 in 4 college-aged women (27.7%) had experienced rape or attempted rape. This staggering number also failed to fully showcase unreported instances of sexual violence, and it didn't mention sexual harassment at all. The journey toward recognizing and addressing the crisis of sexual violence on college campuses was only beginning, a journey that would eventually sweep the country, including Central Michigan University.

|

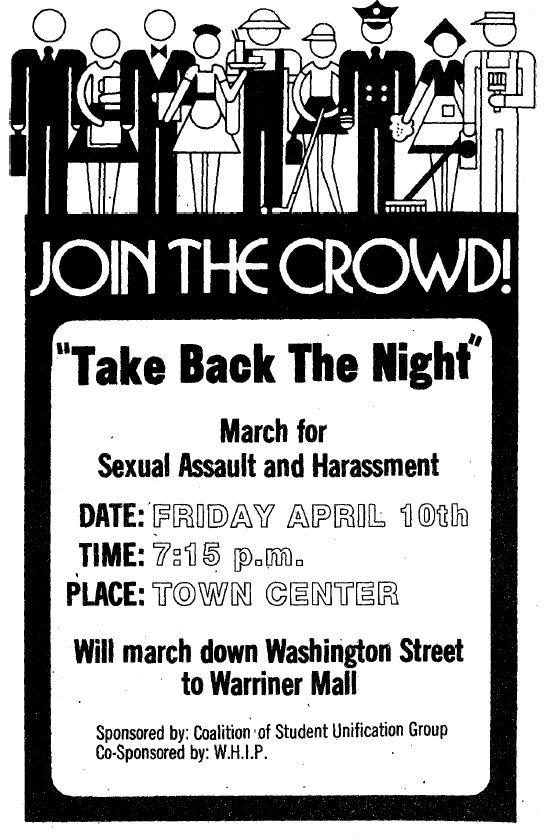

| 1980s Take Back the Night advertisement, from CM Life, April 10, 1981 |

The next major development in Title IX came in 2011, with the writing of a letter that would later be dubbed the "Dear Colleague Letter." Penned by the Office of Civil Rights—a part of the United States Department of Education—the letter states that Title IX requires schools to “take immediate action” after discovering harassment on campus that creates a hostile environment. The Office of Civil Rights detailed the steps universities were expected to take: "In addition to counseling or taking disciplinary action against the harasser, effective corrective action may require remedies for the complainant, as well as changes to the school’s overall services or policies" (p. 15).

Thirty-four years after MacKinnon and several Yale students sued, the United States government committed to addressing sexual harassment and violence under Title IX for the first time. This decision would go on to reshape universities across the country, including CMU.

Although the U.S. Government now offered a tool to combat sexual violence through Title IX, the fight to change the cultures on campus continued. Many of these efforts to improve how colleges and universities combatted sexual aggression began years prior.

For example, CMU advocates hosted the first Take Back the Night Walk in 1981. Take Back the Night has been described as the "oldest worldwide movement to stand against sexual violence" and began as a response to violence against women in the 1970s. Through protests, rallies, and marches on college campuses and in wider communities, Take Back the Night generates awareness about sexual violence and aims to end it. In 1972, the same year that Title IX passed, the first national Take Back the Night was hosted on the campus of the University of Southern Florida, where women carried witches' brooms and protested for increased safety and resources.

Fewer than ten years later, CMU hosted its own Take Back the Night, "a candlelight march through town at dusk symbolizing the fear women have of walking the streets alone at night." A stand against sexual assault and domestic violence, these Take Back the Night events are an opportunity for "men and women from across campus [to] gather to march, demonstrate, and support each other in the effort to eradicate violence and abuse."

Take Back the Night, 2017, CM Life

The tradition has carried on more than forty years at CMU, representing not only the continued violence that women face, but also the continued passion and dedication of students and advocates. CM Life documented the 2017 Take Back the Night march, which showcases how the legacy of CMU's students and women lives on. Today, Take Back the Night continues to "be the resounding cry—take back the fear of darkness and of walking the streets alone."

CMU also hosted an event called a Slut Walk for the first time in 2013, organized by the Organization of Women Leaders (OWLs) on campus. The Slut Walk is an international protest against sexual violence and sexual profiling. The idea for the walk was sparked after a Toronto police officer told university students that if women wanted to avoid sexual violence, they should start by not dressing like “sluts.” The incident sparked international outrage and echoed larger issues of sexual aggression and victim-blaming.

|

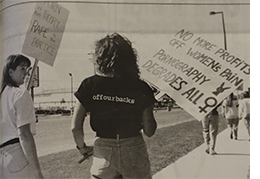

| Protest against Playboy on campus, from CM Life, October 7, 1992 |

It also led to an increased awareness of the role of sexual violence in campus gender discrimination. Passionate students at CMU protested against this sexual discrimination by forming their own Slut Walk, in which students marched and carried signs through the main section of campus. This has become an annual tradition scheduled to continue through 2022 and beyond.

Despite Title IX and the tireless work of advocates, sexual violence and aggression continues to plague college campuses, and it disproportionately affects women. 1 in 5 college-aged women will be assaulted, and sexual violence is far from eradicated on campuses. Creating confusion and complicating this epidemic further, the U.S. Department of Education under Secretary Betsy DeVos issued 2,000-pages worth of changes to Title IX in 2020, greatly narrowing the definition of sexual harassment.

In response, the Office of Civil Rights and Institutional Equity (OCRIE) at CMU expanded its own sexual misconduct policy to continue to protect students. In addition to that effort, CMU student Elise VanParis created the Title IX Task Force in collaboration with the Feminist Leaders on Campus (FLOC), a new iteration of OWLs. The taskforce aimed to educate the CMU community about the U.S. Department of Education's changes to the scope of Title IX and push for transparency from the university.

Nearly five decades after the passing of Title IX, the impact and legacy of this landmark legislation are still being debated—and discovered. Although sexual aggression and violence continues to plague college campuses, CMU students and advocates also continue their fight for equity, safety, and progress.